open main page for all woods open page 2 for articles

AGGREGATE RAYS

Sometimes, in a few different woods, medullary rays will, for some reason, clump together to form what appears to be an excessively wide ray, quite unlike the other rays common in that particular wood. I have not researched the range of width of such aggregate rays but my own experience is that it can be from about 6 or 8 to at least 30. The phenomenon of aggregate rays occurs most often in alder but is also seen American hornbeam and possibly others. Samples are shown below of both. Also, sometimes aggregate rays can be seen in the face grain if you know what to look for. Examples of that are also shown below.

Aggregate rays have a fuzzy look when viewed with at less than about 30X but when viewed at 100X or more the "ray" resolves to

- several individual uniseriate rays, each separated from the next by single rows of cells or a small number of rows of cells.

- a spaghetti-like mix of uniseriate rays twisted among each each other and with other tissue mixed in

Examples of both are shown below.

Sometimes, but not always, the aggregate rays cause an indentation at the beginning of a growth ring. These indentations would normally appear to be the spiky form of indented grain. The indentations are pulled inward towards the pith of the tree just as they are in indented grain, but they are generally smaller than actual indented grain. The rays are noded at that point, "noded" rays being the formal name of rays having a bulge at the point where the aggregate ray crosses a grain line. Noded rays are not limited to aggregate rays but seem to often occur along with them.

Aggregate rays can be either of:

- easy to spot in the end grain because of their obviously "excessive" width

- very hard to make out because they just blend in with the rest of the wood because they have similar or identical color

A point of considerable possible confusion is that there are other woods that clearly SEEM to have aggregate rays but in the literature they are discussed, not as having aggregate rays, but rather as having "rays of two different sizes". That is, it is clear, and is recognized, that they have very small (uniseriate) rays and then much larger rays that appear to be aggregate rays but are just listed as a second size of ray. Oak and beech are prominent examples of this and they are shown with details at the end of this article with further discussion.

Examples:

All of the samples shown here are 1/2" x 1/2" end grain cross sections, shown here at about 6X (depending on your screen resolution)

- numerous aggregate rays of moderate size, in alder, showing grain indentations, visible without magnification

- numerous aggregate rays of moderate size, in alder, showing grain indentations, hard to see without magnification

- several extremely wide aggregates rays, in alder, showing grain indentations, visible without magnification

- numerous aggregate rays of moderate size, in alder, with small grain indentations, hard to see without magnification

- several aggregate rays of moderate size, in alder, with small grain indentations, hard to see without magnification

- numerous aggregate rays of moderate size, in alder, with almost no grain indentations, barely visible without magnification

- several aggregate rays of moderate size, in alder, hard to see without magnification and with minimal grain indentations

- sparse aggregate rays of small size, in alder, almost impossible to see without magnification and with essentially no grain indentations

- numerous fat aggregate rays in hornbeam, visible without magnification and with occasional slight grain indentations

- numerous fat aggregate rays in hornbeam, visible without magnification and with no grain indentations

- numerous medium sized aggregate rays in hornbeam, visible without magnification and with no grain indentations

- numerous small sized aggregate rays in hornbeam, not visible without magnification and with no grain indentations

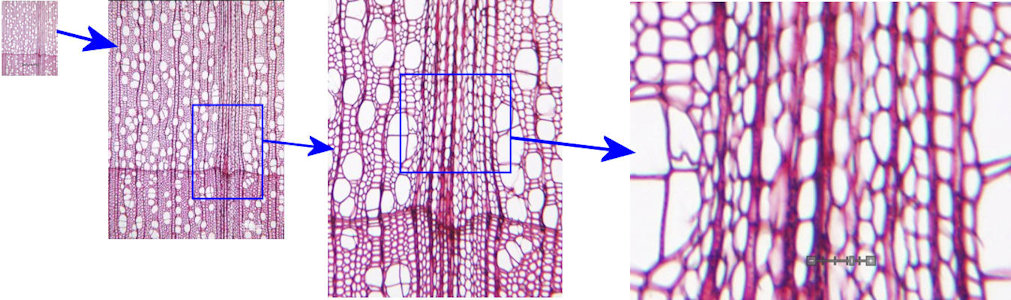

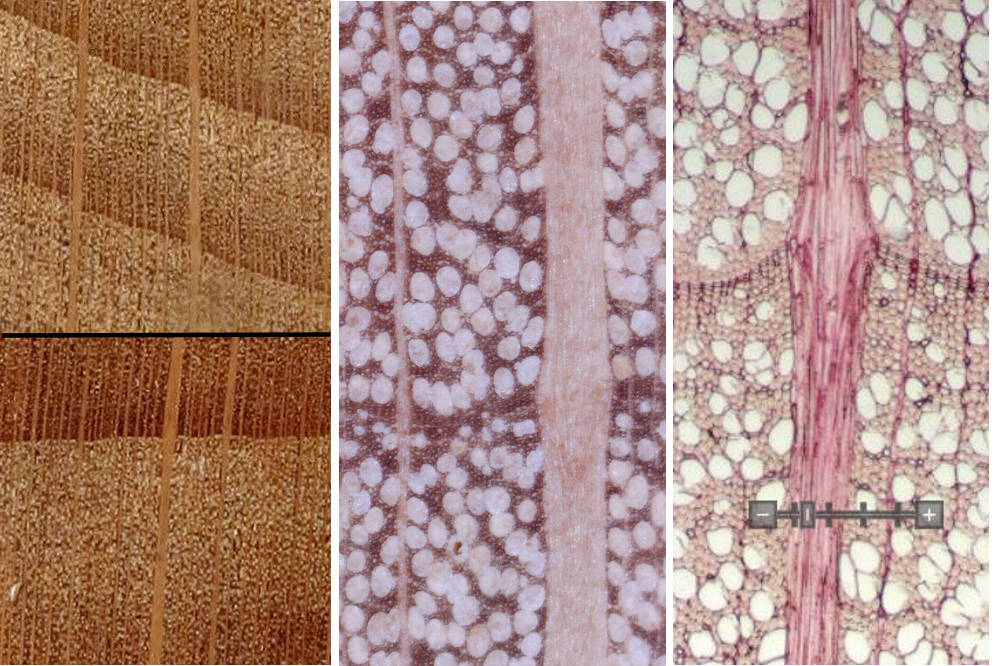

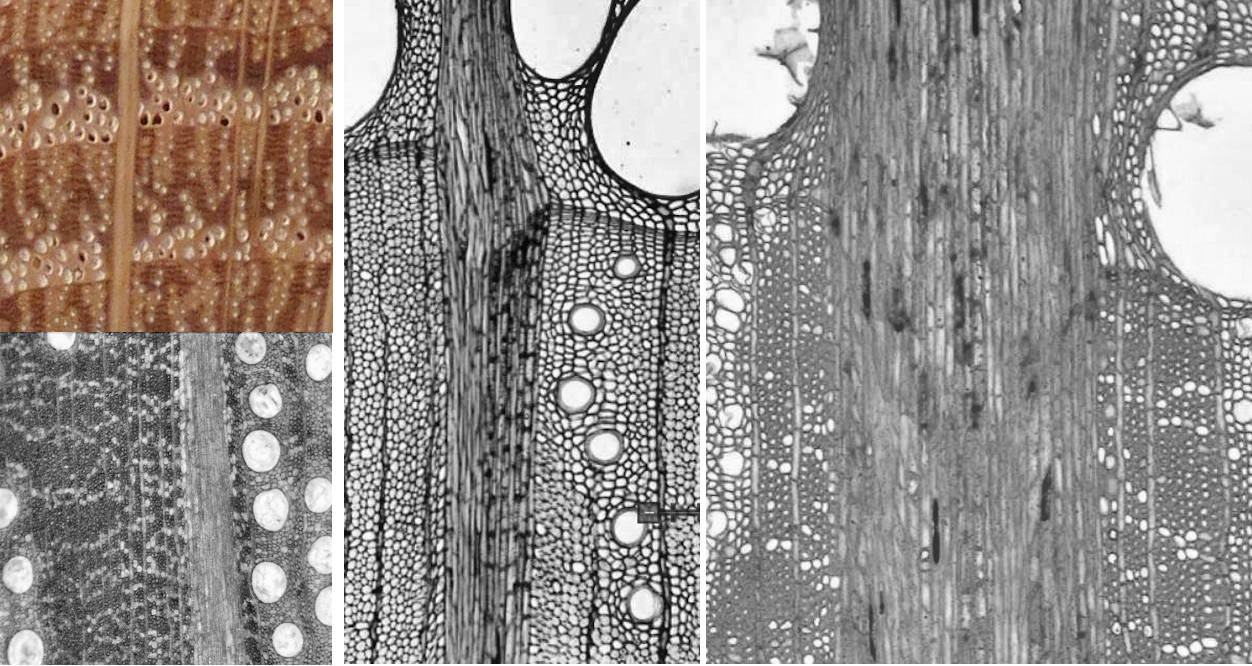

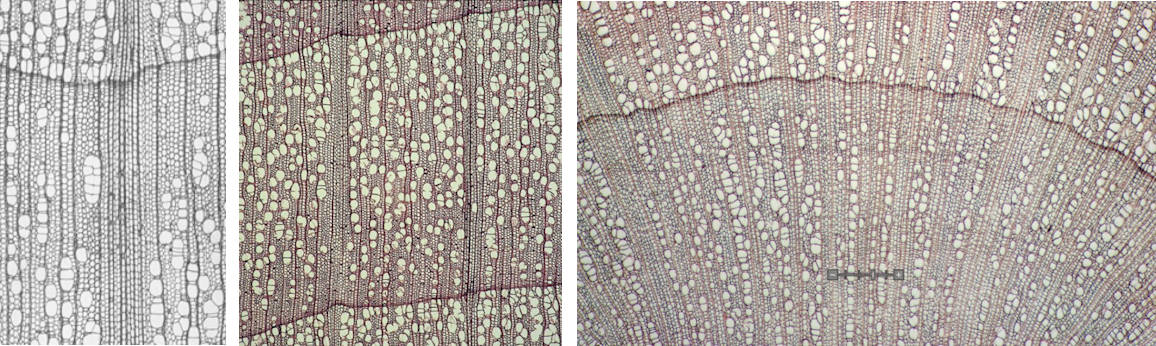

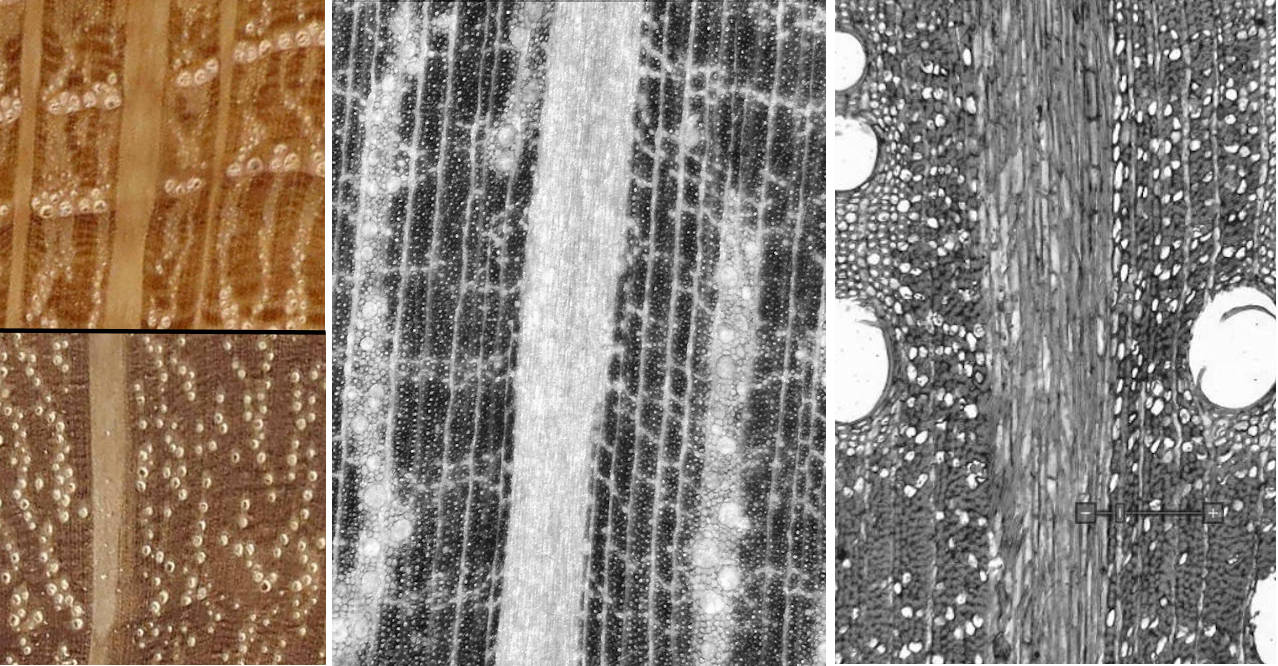

Various magnifications of an end grain of alder, starting with approximately 10X. I'm not sure what the upper magnification is but it clearly shows that this particular aggregate ray is actually several normal rays, each separated by a line or a few lines of normal parenchyma cells. The middle image also shows clearly the thickening that often occurs where an aggregate ray crosses a growth ring boundary plus the slight indentation that it sometimes makes in the growth ring.

a few more alder end grains showing aggregate rays at a magnification that is just high enough to show the composition of regular rays separated by normal parenchyma cells. The last one is an unusual case where there are almost no single rays but a really large number of aggregate rays. These are all from the North Carolina State University anatomy site.

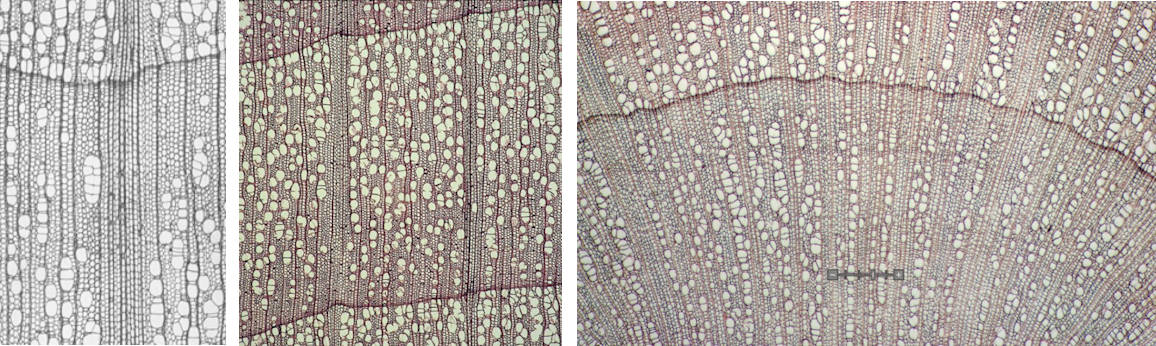

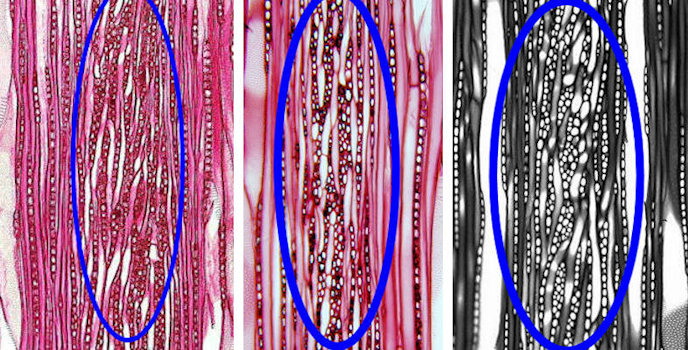

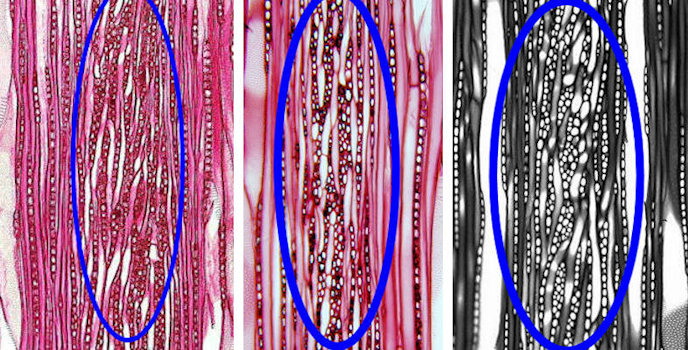

The first three images show aggregate rays in alder, showing how they are sometimes just a "sphagetti" mish-mosh of normal uniseriate rays intertwined with tracheid cells. Also, to show clearly the difference between aggregate rays and very wide normal rays (what you might call multi-multiseriate) the image on the right shows how a normal wide ray (oak in this example) is just a bunch of the "straws", not intertwined with, or separated by, tracheid cells. In all four images you can see normal uniseriate rays off to each side surrounded by tracheids.

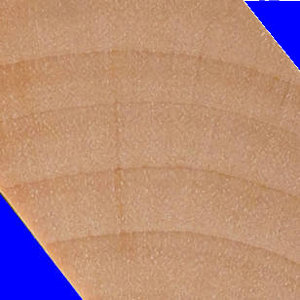

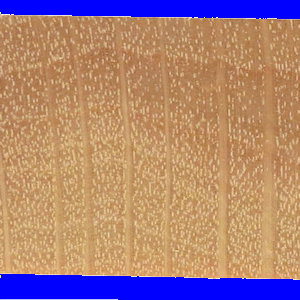

both of these are 3" long face grain areas of alder shown here at about 3X

- aggregate rays --- the dark elongated ovals

- aggregate rays --- the reddish streaks in the middle

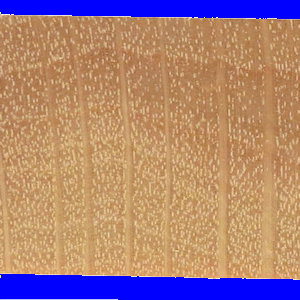

both of these are 3" long face grain areas of hornbeam shown here at about 3X

- aggregate rays --- numerous dark streaks

- aggregate rays --- one fat dark streak

Woods that APPEAR to have aggregate rays but actually don't

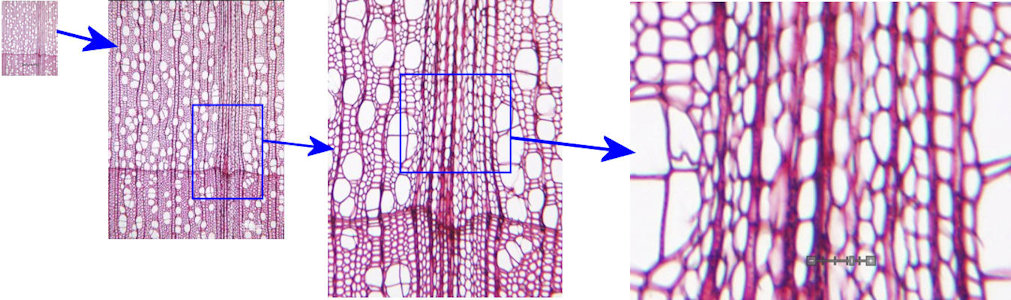

As stated above, there are woods that clearly SEEM to have aggregate rays but in the literature they are discussed, not as having aggregate rays, but rather as having "rays of two different sizes". There does seem to be one clear difference between them and aggregate rays, which is the appearance of the large size rays that are not taken as aggregate rays are always ONLY parallel rows of side-by-side, touching, uniseriate rays. In the woods that have aggregate rays, as discussed above, the aggregate rays themselves almost always have either (1) regular tissue mixed in with parallel uniseriate rays or (2) intertwined uniseriate rays AND other tissue mixed in. Only on very rare occasions do actual aggregate rays have the uniformity of the larger rays in the woods being discussed here.

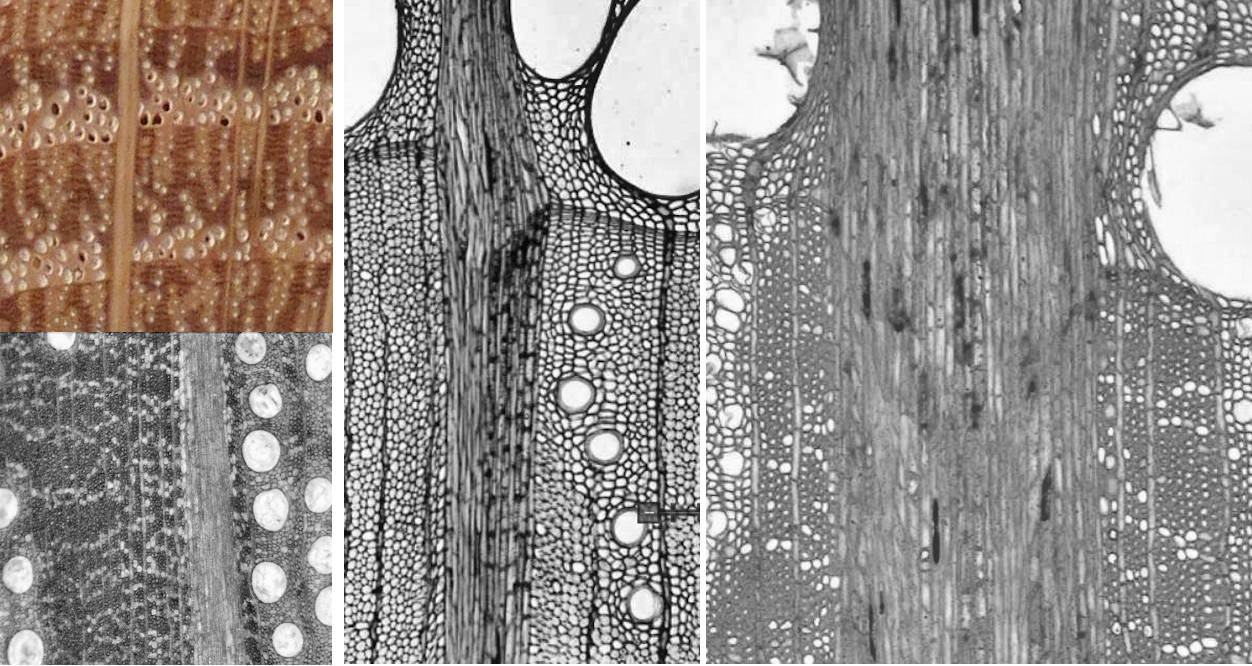

Here are some examples of beech and oak showing this. Sorry about the very large size of these images but that was necessary to even come close to being able to see the large rays clearly.

In each of these you can see (not at all in my 12X samples, just barely in my 200X and 300X samples and fairly clearly in the reference site samples) that the large rays are indeed made up of contiguous uniseriate rays.

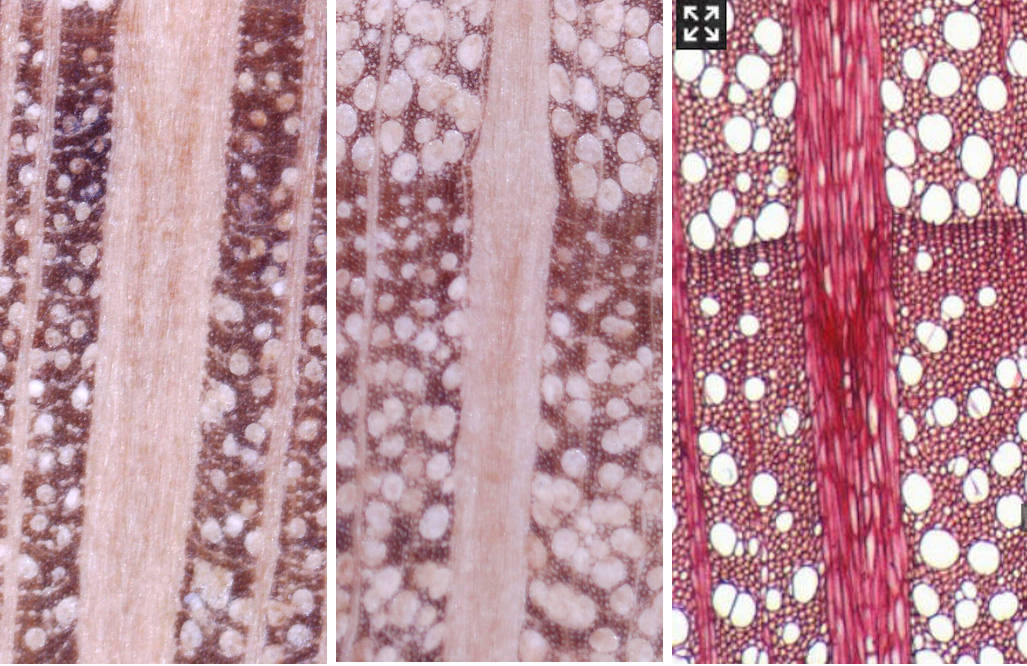

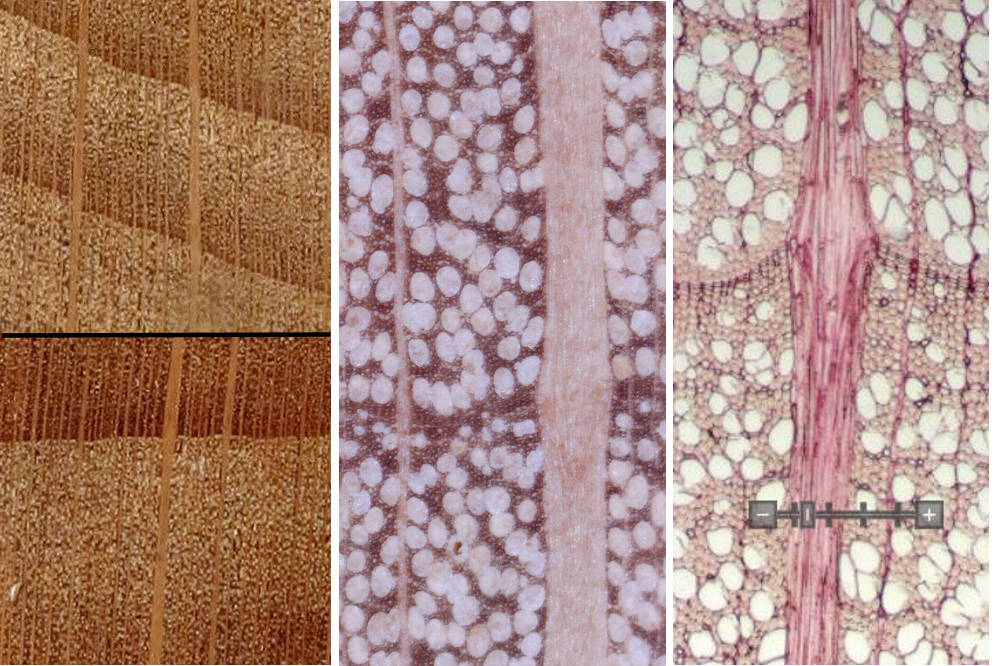

BEECH: two of my 1/4" x 1/4" end grain samples, one on top of the other, shown here at 12X, followed by one of my high magnification samples shown here at about 200X and then a sample from a reference site shown here at approximately 200X

BEECH: two of my high magnification samples shown here at about 200X and then a sample from a reference site shown here at approximately 200X

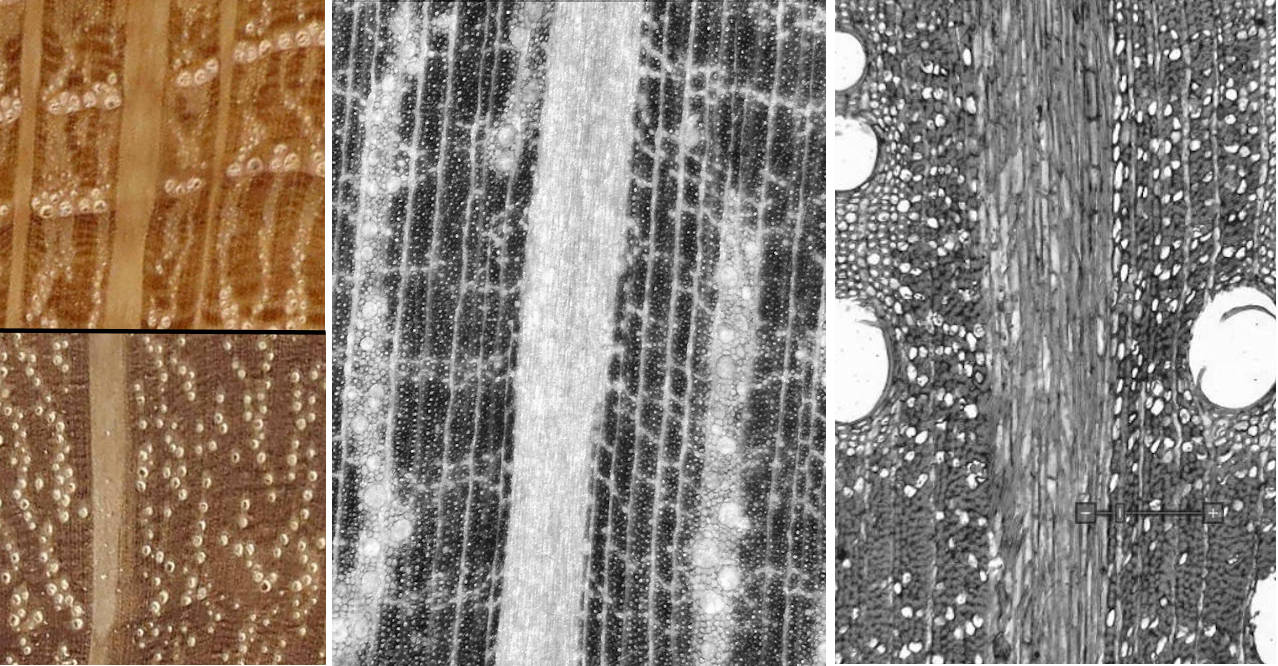

OAK: two of my 1/4" x 1/4" end grain samples, one on top of the other, shown at 12X, followed by one of my high magnification samples shown here at about 200X and then a sample from a reference site shown here at approximately 200X

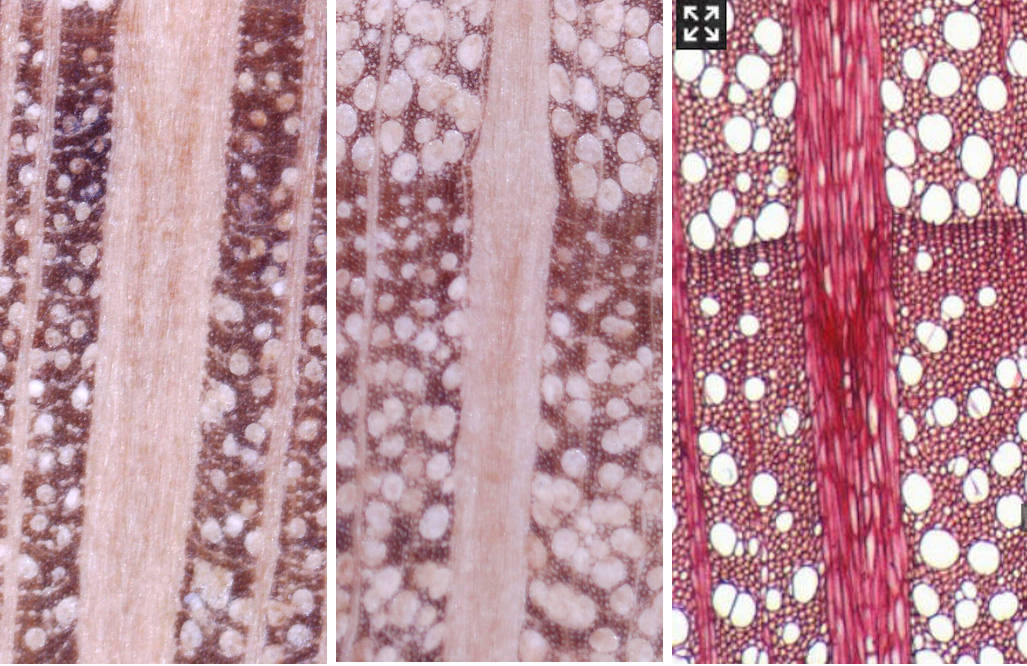

OAK: one of my 1/4" x 1/4" end grain samples shown here at 12X and below it a small sample from a reference site and then two samples from a reference site each shown here at approximately 200X

Just for grins, here is one of my own high magnification samples shown here at 300X and a reference site sample, also shown at approximately 300X. These make it very clear that these large rays are contiguous uniseriate rays with no intervening tissue and no intertwining.