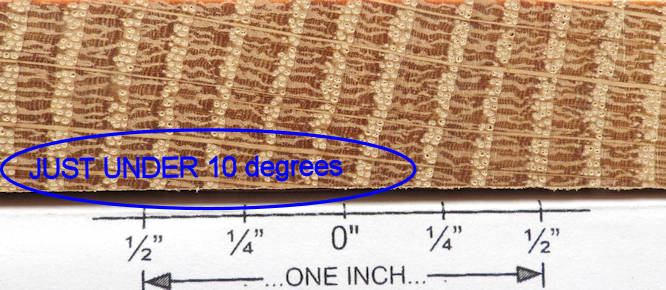

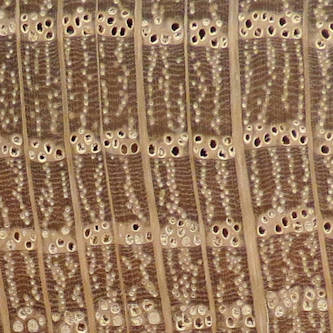

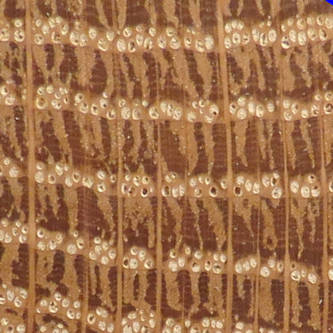

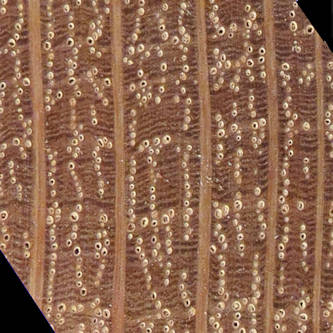

| 1/2" x 1/2" end grain cross sections | ||

|

|

|

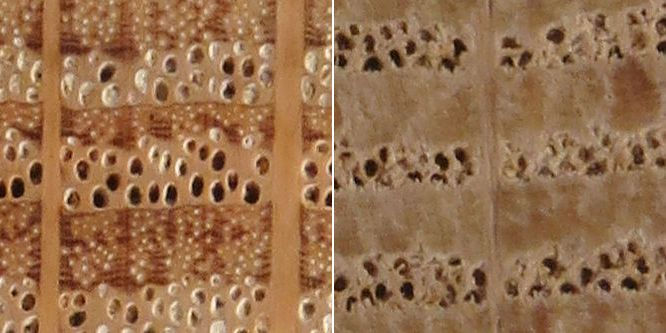

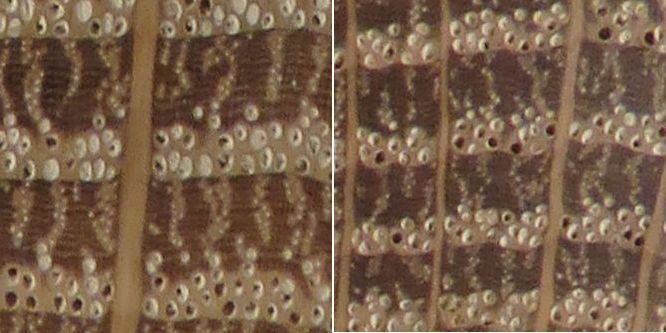

| red oak --- ring porous with large earlywood pores, very little tyloses (but some pores clogged with dust) |

white oak --- ring porous with large

earlywood pores (a few open pores but most clogged with tyloses) |

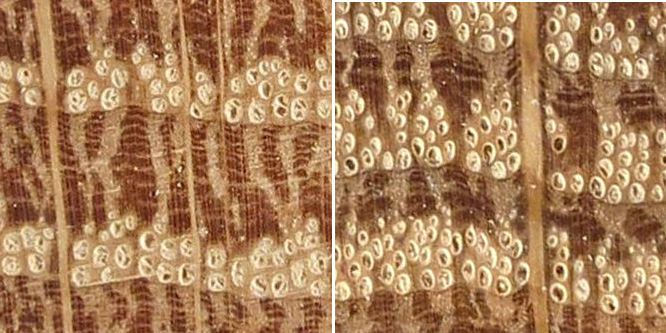

live oak --- diffuse porous with no row of earlywood pores (can be red oak or white oak) |